My Psychological Experience of Transitioning from Drug Addiction and Criminality to Becoming a Productive Member of Society By Michael Mooney, MA, LLP, CAAC-R, CCS, CCJP, NCGC

The following is “chapter one” in my thesis/research paper for my Master’s of Arts degree in Clinical Psychology in 2002. This chapter will examine my transition from the despair of living with a drug addicted, criminal lifestyle to becoming drug-free and happily involved in the “recovery process.” The overall focus of this thesis will be on addicts who have broken the bonds of chemical dependency through the 12-Step programs of recovery and found a new way to live free of addiction to both drugs and crime. “The abuse of psychoactive substances is the number one health and social problem of our times. The personal misery and societal loss connected with it are inadequately estimated by traditional measures” (Franklin, 1992, p. 1).

CHAPTER ONE

Smash! Crash! OPEN UP! IT’S THE POLICE! As my front door was being torn from its hinges I once again pondered the events that led to me being the target of another drug raid. It was in the summer of 1987 and I was being arrested. I was told that earlier in the day I unwittingly sold drugs to an undercover police officer. This drug sale involved 45 pounds of marijuana. Later that night, while locked in a cell with the beginnings of narcotic withdrawal setting in, I recall thinking that I did not care what happened to me anymore. I was sick and disgusted with myself. I knew that it would be some time before I made it to the streets again and I felt that my miserable life was not worth the pain of living. I had felt this way before. This was not my first drug related arrest. I had been a heroin addict since the late 1960’s with prior police problems that began way back in my childhood. Sitting alone in jail, I reviewed my plight.

I was born on March 7, 1952. My mother struggled to raise me, along with my two older brothers and one younger brother. We resided in a low income “housing project,” in Detroit. I grew up with the Baby Boomer Generation which followed the ending of World War II. My father was an alcoholic and the first time that he abandoned our family was shortly after the birth of my younger brother. After my father left, my mother received welfare (Aid for Dependent Children) and I was raised in poverty. As a young child, I felt uneasy with myself. I always had feelings of being shy around other people and I would often escape into my own fantasy world of make believe. While growing up, I remember that all of my clothing were “hand me downs” from my two older brothers. Most of the other residents in the housing projects were also single parent, low income/welfare families. My brothers and I were raised as “poor kids” and, as an example; I recall that for Christmas we would sometimes only get “Goodfellow packages” that were distributed by the local newspapers.

When my mother received her monthly ADC checks, she would give us boys each a nickel allowance. A nickel did not go too far, even in the 1950’s. Somewhere around the age of four, I developed a scheme with some other kids from the housing projects that we simply called, “The Trick” which involved my going up to and knocking on various neighbors’ doors and saying, “Hello Mrs. Smith, my mother sent me over. She is standing in the checkout line at the grocery store and she is 25 cents short from paying her store bill. She wanted me to ask you to loan her the 25 cents and she will pay you back when she gets her next check.” Most of the time, the neighbor would give me the 25 cents. What I was banking on was that because the amount was so small, these neighbors would forget about it and, consequently, never get around to asking my mother for their money back. Of course, my mother never knew of the debt that I was incurring in her name. Soon after, I was putting some of my friends up to doing “The Trick” on their neighbors, too. At the age of five, I was caught for the first time shoplifting toys from a local Five and Dime store. What compounded this problem was the fact that I was skipping kindergarten. I remember the policewoman that picked me up from the store and took me home to my mother. The policewoman expressed a real concern that I was “so young” to be in trouble. The spanking that I got for this theft merely redoubled my efforts to be craftier the next time and try to avoid getting caught. I believe that my mother did the best she could in raising my brothers and me. It is interesting to note that, out of a sib-ship of four brothers, only I became an addict and a criminal.

In 1961 I turned nine years old, and that summer my family was forced to move from the housing projects. This occurred because, after six years of absenteeism, the authorities finally tracked down my runaway father and charged him with abandonment. He was court ordered to return to our family and his presence at home made us ineligible to continue to live in the housing projects. Now that my father was back as the head of the household, our family was taken off of welfare. The problem was that because my father was an alcoholic, he had great difficulty holding down a job and thus, did very little to really support us. As the early 1960’s progressed, I started skipping school regularly and hanging out with other kids who exhibited similar delinquent tendencies. I liked running the streets because of the sense of independence it gave me. It was about this time that “glue sniffing” was gaining popularity as a way to get high and I remember sniffing glue on a daily basis, as well as drinking alcohol. For me, getting high was an activity that was similar to escaping into my childhood fantasy world. While growing up, my “street friends” had more of an influence on my behavior than did my mother or the school system. There was an odd kind of mutual respect that my friends and I shared together. Simultaneously, we were outwardly defiant of all authority figures, including parents and school teachers. We were a motley crew of misfits, druggies, and losers. I soon dropped out of school and left home altogether. I developed a petty criminal lifestyle and was arrested at the age of 12 for juvenile delinquency. This arrest resulted in my being made a “ward of the court” and, subsequently, I was placed in and out of juvenile detention centers for the next five years. In between these detention centers, I continued with my substance abuse. For me, getting high was a real blast! When I was under the influence of alcohol and other drugs, the sense of well-being and aliveness that I experienced was unmatched by any other sensation or feeling that I have ever felt. When the drugs wore off I always suffered from a sense of low self-esteem and feelings of worthlessness. Without the drugs, I always felt hollow, as if something was missing. The drugs induced a feeling of adequacy, or even superiority in me.

My inner turmoil was being matched by the outer turmoil of the nation around me. Throughout the 1960’s, the national social backdrop played an influential role in my coming of age. To many, the most prominent decade of the 20th Century was the 1960’s. These were times of great social change. On one front there was the Civil Rights Movement, while on another front our country was involved in an unpopular war in a remote country called Vietnam. Both of these issues helped mold a new generation of Americans, including me. This new generation had various names such as the Baby Boomer Generation, the Love Generation, the Now Generation, and even the Pepsi Generation! When I was 15 years old, I ran away from a juvenile detention center in rural Michigan and came back to my old Detroit neighborhood. I quickly identified with various groups that were in reaction to the times such as, the “drug culture,” the “counter culture,” and the “underground.” Collectively, these groups represented the “hippie movement” which would later be called the Woodstock Generation. We developed our own causes which included our own form of expression that the previous generations had difficulty in being able to relate to or understand. This was neatly labeled as the “Generation Gap.” We talked and acted differently, using expressions that made our parents wonder. “Bad” was good and “far out” had nothing to do with distance. We were dressing differently and listening to different music. The English invasion of the music scene set the stage for new fads in clothing and hairstyles. I was swept up in the excitement of the times. As I recall, my own dress - bell bottoms, bright colors, psychedelic prints, and tie-died tee shirts - was the order of the day.

As for the music itself, the lyrics that were related to drug using or had an anti-establishment theme were the ones that had the most influence on my friends and me. Along with these fads, a new wave of recreational drug use was sweeping across the nation. At the forefront of this wave was the seemingly benign use of marijuana and LSD. I soon graduated from sniffing glue and drinking to smoking marijuana and ingesting hallucinogens on a regular basis.

About the time of the Detroit riots in the summer of 1967, I went through a startling transformation. I went from a newly drug-addicted juvenile delinquent to a starry-eyed “flower child.” I got deeply involved with the local hippie scene. This was a time of rock and roll concerts, black lights and posters, free love, and peace signs. The ongoing war and the recent race riots across the nation left a lot of people feeling bitter and angry and I developed a political awareness of the discontent shared by many. I saw the Civil Rights Movement as the “haves versus the have nots,” focusing on issues of inequality. During the Vietnam War controversy, I sided with the conscientious objectors who were protesting the war. We pitted ourselves against the mighty military/industrial complex of corporate America. There was a general air of disillusionment spreading over the land and some people began talking defiantly about having a revolution! The Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960’s saw the advent of mass demonstrations in our cities’ streets and paved the way for similar demonstrations against the war in Vietnam. What started as my involvement with the peace and love movement, changed with my active participation in the anti-war movement. I became openly rebellious of our government’s policies and its involvement in the war in Vietnam. I viewed the police as “pigs” and I grew to be further alienated from society at large, whom I labeled as the “straight people.” Young people all around me questioned, and then rejected, the values and decisions that our parents’ generation had set in motion. I became involved with the more radical groups such as, the White Panthers (a spin-off from the Black Panthers), the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and I wanted to join the militant arm of the SDS, known as the Weathermen. Throughout 1968 and 1969, I was an urban revolutionist and I was involved in mass demonstrations against the war, as well as secretly planning militant acts against “the pigs.” Politically, I called myself a “leftist,” and “Power to the people!” became my slogan.

About this time, I was introduced to heroin which I fell in love with as the ultimate high. Logically, to me, it seemed that the more serious my anti-social/rebellious behavior became, the more I needed to experiment with the “hard drugs.” Concurrently, my father abandoned our family again which affected me on a deep, personal level. In a way, I felt responsible for my family “splintering off” in different directions. I thought that, because of my juvenile delinquency and radical appearance, I was a growing embarrassment to the rest of my family. I think that my dad got tired of the police coming to the door.

In late 1969, at the age of 17, I was arrested for heroin possession and placed in an adult prison. When I got out in 1971, I briefly drifted back into the local underground hippie scene. It was somehow different. Not only was my mood and situation changing, it seemed to me that the whole Woodstock Generation was on a downward spiral. The Vietnam War was beginning to wind down, as was the talk of having a revolution in the streets. Coming out of prison, I vaguely felt like an unemployed revolutionary, lacking a sense of purpose or direction. In the previous time span of about five years, I went from being a child, to a juvenile delinquent, to a hippie, to a militant, to a heroin addict, to a drifter without a cause. I was easily influenced by the passing fads. My starry-eyed illusions and fantasies from the mid-1960’s were being challenged. The drug deaths of Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Jim Morrison were in sharp contrast to my earlier sense of fun and excitement that I previously associated with the hippie scene. My use of heroin changed my perceptions to the point of numbness and lack of caring. I began using heroin more and more to medicate and anesthetize my emotional pain. I became caught in a vicious cycle of using dope to live and living to use dope. In the early 1970’s, I turned to drug dealing to support my growing dependence on heroin.

I was in my 20’s now and I had still never had a real job. I occasionally played music with other drug addicts and for a while I imagined I would become a rock and roll star. I played congas and bongos. My regular involvement with drug dealing kept me in contact with other addicts and I would sometimes do other crimes with them to help feed my addiction. My life became increasingly dysfunctional. I had several relationships with women who also had drug problems. Mostly, my relationships centered on sexual activities and never developed into any meaningful partnerships. I was extremely shallow and stunted in my adult development and thus, I was superficial in my ability to form meaningful, caring relationships. During these times, my personal mission statement was, “play hard, die young, and try to leave a good looking corpse.” I was getting high and doing crimes on a daily basis and I felt that I was rapidly approaching a “burn out” existence.

Throughout the rest of the 1970’s and into the 1980’s I was becoming increasingly hostile, resentful, and isolated. I was very self-centered and sick. Physically, I was unhealthy; emotionally, I was dying; and spiritually, I was dead. I could have hired on as an “extra” in the Night of the Living Dead movie. I remember thinking that I had no problem with the concept of simply using dope until I died. The problem came when, year after year, I did not die! Instead, I found myself rapidly approaching middle age. I never really expected to get old. How many old junkies do you see around? Not many. They either die off or go to prison. I somehow managed to exist in this twilight world of drugs and crime for a few more years, quietly plying my criminal trade while living on the outer fringes of society. For a while, I ran a highly profitable and successful drug dealing operation. I had several addicts working for me and I developed a strange sense of self-importance that was associated with my drug dealing identity. Addicts in need of a fix would show me respect! Street hookers sometimes called me sir! It was a shame that I was my own biggest customer.

In 1980 I got married to an addict and we sometimes would talk of “going straight,” but nothing ever came of these talks. The drugs were the central focus of our relationship. I lacked the capacity to be intimate or monogamous with her, for my primary relationship was with the drugs. I habitually turned to the drugs for emotional comfort, similar to the way that other people turned to their spouses for such needs. I relied on the drugs to support me through the good times and the bad times. Metaphorically, I “wined and dined” the drugs and I sought the soothing companionship that the chemicals provided. Of course, as with any real relationship, I had my break-ups, followed by my make-ups. Sometimes late at night, in a rare moment of introspection, I would reflect on my addiction. I would softly say to my pillow, “This is it, I’ve got to stop, and I need help!” These were the break-up moments. I would even throw away my syringes and other drug paraphernalia, only to find myself later in the day “making up” by going to get high again. I carried on a stormy love affair with a variety of chemicals for almost three decades of my life. Because I did get married while simultaneously being “wedded to the chemicals,” the best I was capable of offering my wife was to be a “two timer!” The drugs were my primary relationship and my wife was a distant second. We managed to stay together, bonded by our mutual sickness, until I was arrested for selling drugs to the undercover police officer in 1987.

I had a few other arrests during the early 1980’s, but nothing that my attorney could not handle. What made this drug bust different was the fact that I was already on bond for another drug arrest that had happened earlier in the year. Subsequently, my attorney was fresh out of new ideas, and, because I was arrested while I already had another pending drug case, I was not eligible for another bond. It became apparent to me that I was not getting released and I was going to have to “kick” my heroin habit in jail, again. The day after I was arrested, I was transported to the Macomb County Jail. I was feeling very ill with the withdrawal symptoms and was not looking forward to the next several weeks of kicking my habit “cold turkey.” My withdrawal symptoms included severe diarrhea, vomiting, muscle cramps, cold sweats, and insomnia. We addicts refer to the simultaneous diarrhea and vomiting as, “leaking from both ends.” I felt miserable and the fact that I was on my way to prison again added to my misery.

The worst thing about my kicking cold turkey is the insomnia. One night, as expected, I was not able to sleep and I was tossing and turning around on my cot trying to get comfortable. My mind was racing with the thought that I was going to die from the sheer agony of the physical withdrawals. It was about then that I noticed an old copy of a raggedy, dog-eared, coverless Readers Digest lying on the floor of my cell that was probably left by a former inmate. It looked like I felt. Because I could not sleep, and to temporarily take my mind off of my withdrawal sickness, I got up from the cot and sat in the corner of my cell where enough light was coming through the cell door from the hallway to illuminate the pages. I draped my sweat soaked sheet over my goosefleshed shoulders. I knew it was going to be a very long unpleasant night, so I decided to read. As I flipped through the pages, reading the various articles, I became aware of a sensation of estrangement from myself.

The Readers Digest seemed to bring to life the “American Experience” as experienced by “normal” people. More so than many other publications I have read, this Readers Digest seemed to show me a “slice of life” that seemed to be taken right from “Anytown, USA.” Some of the stories were about everyday small town life, while other stories were amusing anecdotes about chasing the American dream. Whether it was the jokes from “Humor in Uniform” or from the “College Life” sections to name a few, I got a strong sense of what other people were experiencing, as they were going about their daily affairs. Mostly, it seemed to be pleasant experiences for them. Be it the big stories, the little stories, or the funny “one liners,” collectively, this magazine was painting a picture of the American dream for me as seen through the eyes of everyday “non-addicted” people. Articles delineating how to lower your monthly mortgage, or, where to get good automobile insurance, for instance, illustrated for me the important topics on the minds of this magazine’s typical subscribers. Here and there were a few heartwarming stories about people overcoming the obstacles that were occasionally thrown at them, like curve balls in the game of life. Perseverance appeared to be a reoccurring theme in many of the articles.

While I was reading I was vaguely reminded of “mom, baseball, and apple pie.” Maybe it was a peculiarity of my withdrawals, or the emotional tangent I was going off on, but I thought I even saw a “slice of apple pie” in the countless advertisements, too! Ads, such as, “the good folks at Kraft are coming out with a new kind of cheese,” or, “Sears is now proud to announce that it is marketing a new garden implement that will cut your yard-work time in half!” ignited a small light bulb inside my head.

It started off like a dim, two-watt bulb, faintly glowing in the deep dark regions of my mind. I was having “an awareness.” My internal voice clamored, “I’m starting to really screw up here! I am deviating away from the American dream!” Like a bolt of lightning, it occurred to me that all these years I have been slowly drifting away from “mainstream society” courtesy of the dope use and crime. I said to myself, “I am a misfit! I don’t own a house that needs mortgaging, nor do I have a garden that could use a Sears chainsaw, or whatever that damn garden gadget was in their ad.” I felt more like an alien from outer space than I did a life long resident of this country. I became aware that I was totally out of step with the rest of humanity.

With honest introspection I saw that nothing in this magazine really pertained to me. I could not remember the last time that I bought Kraft cheese or even shopped in a grocery store, for that matter. I never had legal automobile insurance, either. I asked myself, “Just what the hell have I been doing for the last 30 years?” Reading story by story long into the night, it dawned on me that as many of my countrymen were going about their business of pursuing the American dream, I was going about my business of pursuing a miserable existence back in prison. I felt my life to be a total loss. I remember that my eyes moistened and I was overcome by a deep sadness. The pain I felt transcended my withdrawals. It was the start of a wake up call.

I was eventually found guilty of selling the 45 pounds of marijuana to the undercover cop and I was sent to prison for the next several years. As the time passed for me in prison, I could not get away from the thoughts that I had with the Readers Digest experience. Sometimes I would hear a disembodied voice in my head saying, “You are really screwing up your life now” or “...you worthless piece of crap.” I felt vaguely haunted by the images from that old magazine.

As I continued to do some self-assessing during those prison years, I cringed at the growing awareness that, although part of my problem was obviously my drug use and crime, I discovered another part of the problem was that I developed a deep dark twist to my personality. Somewhere over the years, I was losing my capacity to feel normal. I was feeling alienated from society and I disliked myself. Without the drugs, I was somehow less than zero. My appearance reflected my alienation: I was wild eyed and disheveled, with long hair and a scraggly beard. My self-awareness here did not immediately translate into a solution, but it was a beginning. I cut my hair and shaved.

In the summer of 1990, the Michigan Department of Corrections transferred me from the state prison in Jackson to a Community Corrections Center in Detroit to serve the last year of my sentence. The corrections center was also called a “halfway house” which is a residential setting for minimum security inmates run by the Salvation Army. The staff consisted of both Salvation Army employees and prison guards. I was 38 years old when I arrived there and, right off the bat; I was confronted by a challenging problem. I was expected to get a job and to also save money for my eventual parole. Since I had no trade, no vocational skills, nor any previous work experience, these expectations presented a real obstacle to my successful integration into the community. I was a dope dealer and a hustler! Compounding this problem was my lack of an education. I had dropped out of school in the sixth grade. My prospects for employment looked grim. This dilemma awakened me further to my long term existence on the fringes of society and it became another way for me to measure just how “out there” from normalcy I had become. I was feeling lonely and depressed. I was not making a smooth transition from prison life to living in the halfway house. I briefly tried to find my wife and discovered that she was living with another man. We lost touch with each other while I was in prison. We eventually divorced. I was in familiar pain. To soothe myself, I began to secretly drink alcohol, which was strictly prohibited in the half way house.

I remember telling myself that as long as I stayed away from the drugs, I was still doing good. However, I quickly fell into my old behavior of medicating my emotional pain with other chemicals and I was soon caught through a random urine drug test at the halfway house. I was hitting my bottom ...again. I was then ordered to enter a drug rehabilitation program that was affiliated with the halfway house. Early on in my drug treatment, I remember being told that I suffered from the “disease of addiction” and not from a moral deficiency. I found that to be an interesting notion. Two weeks into my treatment, drugs were smuggled into the ward and I got high again. That was January 14, 1991. I felt very guilty and uncomfortable about using there.

That damn Readers Digest was back! For me to get high on the streets was one thing, but to get high in a drug treatment program was obviously sick and twisted behavior! “This is it, I’ve got to stop, I need help,” echoed a voice in my head. I remember that I started praying for help out of sheer desperation. Even through the drug haze, the information that was being presented to me in this treatment program had started to make sense. The drugs were no longer giving me the emotional comfort that I sought and I felt equally miserable with or without the dope. I was at the end of the road.

The very next day, January 15, 1991, I made a conscious commitment to myself to try and stay clean and sober. Still in treatment, I was introduced to the 12-step concepts and philosophies of both Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and the Narcotics Anonymous (NA) programs and I started to attend NA meetings on a regular basis. Narcotics Anonymous at its simplest level, is a fellowship or society of men and women for whom drugs had become a major problem. The NA program promotes total abstinence from all psychoactive substances, to include alcohol.

A passage from the NA literature says:

Narcotics Anonymous provides a recovery process and support network inextricably linked together. One of the keys to its success is the “therapeutic value” of addicts working with other addicts.

Members share their successes and challenges in overcoming active addiction and living drug-free productive lives through the application of the principles contained within the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions of NA. The core of the Narcotics Anonymous recovery program is the Twelve Steps, which include admitting there is a drug problem, seeking help, engaging in a thorough self-examination, confidential self-disclosure, making amends for harm done, and helping drug addicts who want to recover. Central to the program is an emphasis on what is referred to as a “spiritual awakening,” emphasizing its practical value, not its philosophical or metaphysical import.

Narcotics Anonymous itself is non-religious and encourages each member to cultivate an individual understanding, religious or not, of this “spiritual awakening.” Narcotics Anonymous is not affiliated with other organizations, including other Twelve Step programs, treatment centers, or correctional facilities. As an organization, NA does not employ professional counselors or therapists. Narcotics Anonymous has no residential facilities or clinics, and does not provide vocational, legal, financial, psychiatric, or medical services. NA has only one mission: to provide an environment in which addicts can help one another stop using drugs and find a new way to live.

(Narcotics Anonymous, internet article)

One day while I was at a NA meeting, I met this man who showed an interest in my “story.” Over time, we began talking and I found that his story was similar to mine. His name was Benny and he had 10 years of staying clean through his participation in the NA program. I really admired Benny for his ability to transform his life after freeing himself from his substance abuse and then successfully completing an addictions studies program at a local university and becoming employed as a drug counselor at Chrysler Corporation. I did not think it was possible for drug addicts to achieve that level of functioning and acceptance in the business world. He told me that if I stayed clean, it might be possible for me to do the same. While I was still in the drug treatment program, I was assisted with attaining my GED and also with obtaining employment.

It was a minimum wage job in a local factory. It was hard work and I was not accustomed to physical labor. I wanted to quit but Benny pointed out to me that despite my low pay-rate, I needed to “hang in there.” He said that this job was teaching me important “employment stuff” that I really needed to learn. Benny saw that the real value in this job was in teaching me how to develop a good work ethic. Up to this point in my life, I rarely got up to an alarm clock, and I was not very dependable or reliable when dealing with other people. I had limitations in my “people skills” and this was apparent at work. I was easily frustrated and I was often argumentative with co-workers. I did not know how to be a team player.

I had many other problems too, and after the NA meetings, Benny would take the time to talk with me about my troubles. He would often tell me to take it “one day at a time” and after we talked, I would usually feel a lot better. He always urged me to “hang in there” and “do not give up.” Benny saw my factory job as being temporary. He offered me encouragement that perhaps my real “calling in life” was to help other addicts and convicts piece their lives back together in recovery. One addict helping another, is the basis of the NA program. I stuck it out at the job and eventually I grew to like working there. I was slowly growing, developing, and changing. The transitioning had begun.

Out of a growing sense of gratitude for my newfound recovery, I started helping other addicts with drug problems. I did this primarily through volunteer work in the halfway house where I resided. This early volunteer work and the advice I was getting from my role model, Benny, led me to make a commitment to pursue a career in the field of substance abuse counseling. In the summer of 1991, I paroled from the halfway house to a hotel room in downtown Detroit.

I continued to work in the factory by day and attended NA meetings at night. At work I was learning new skills which were facilitating my becoming an accountable, responsible, and dependable employee. At the NA meetings, I was learning the value of my being open and honest when sharing my problems with others. I was told that I was “only as sick as my secrets.” I also was keeping an open mind to new possibilities and I had the willingness to follow the suggestions of other recovering addicts.

Integrating my learning from the NA meetings with my learning from the work environment, I felt that I was healing and making significant progress! I was developing a sense of self-esteem and pride in myself for accumulating some “clean time.” The clean days turned into weeks then into months. I began socializing with recovering addicts that I met at NA. Simultaneously, it seemed that I had drifted away from my old “playgrounds, playmates, and playthings” that had been such a big part of my life in active addiction.

Everything was changing for me. I was slowly coming “out of the fog” after almost 30 years of active drug addiction. I had a sensation that must have been similar to the “Rip Van Wrinkle” story in which a man falls into a deep sleep and finally wakes up 20 years into the future. In that story, the man stumbles around out of step and out of time with everyone that he encounters. I often caught myself stumbling over common, everyday life skills and information that was unfamiliar to me. For example, although I was in my late 30’s I never had had a checking account, or car insurance, and rarely did I have a legal driver’s license. I grew up using aliases. I never paid income taxes. I thought “taxes” was the Lone Star State.

In my recovery, I was becoming deeply aware of the under developed aspects of my personality, which included a lack of interpersonal experience and skills. I often felt tongue-tied when talking in front of women. This never happened when I was under the influence of drugs. When I was high on drugs, I used to pride myself on my “gift of gab” with the ladies. In many ways, I felt like a little kid during my early months in recovery. I had to re-learn everything and at times I was overwhelmed with fear. Over time, I slowly began to emulate the positive behaviors that other recovering addicts displayed.

There were good role models all around the NA fellowship, and it was often “monkey see, monkey do” for me. I was learning and growing. I continued to pursue new friendships in recovery and eventually I asked Benny to be my NA “sponsor.” Sponsorship in NA is a process where an older member commits to teaching a newer member how to stay clean and work the 12 steps of the NA program.

I still very much desired becoming a substance abuse counselor and with Benny’s assistance and support, I made that my goal. I studied diligently and, in 1992, I obtained a passing score on the Fundamentals of Substance Abuse Counseling (FSAC) exam offered by the State of Michigan. This was the minimal requirement that was needed to begin apprentice-counseling work.

In January 1993, I obtained employment at a substance abuse counseling agency, as an “apprentice counselor.” Under comprehensive supervision, my duties included delivering individual and group counseling services to some of the agency’s client population. Coincidentally, the clients attending this program were mostly on parole from the Michigan Department of Corrections. Building on my fledgling FSAC credential, I enrolled in a program that was designed to assist me with obtaining the Certified Addictions Counseling-Level II (CAC-II) credential. The Michigan Board of Addiction Professionals (MCBAP) and Western Michigan University oversaw this process. Briefly, the CAC-II program involved my accumulating 6,000 hours of counseling experience, continuing clinical supervision, passing three written exams, and completing 270 clock hours of substance abuse related education.

On December 19, 1995 I completed all the requirements and received the CAC-II credential and then I was allowed to drop the “apprentice” from my addictions counselor title. The CAC-II credential designates that I have reciprocity with all other member states and nations that conform to the International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium’s (IC&RC) guidelines for Alcohol and Other Drug Counselors. This was a fine feather in my cap!

My world was changing. Early in the 1990’s I moved out of the downtown Detroit hotel and rented a room from a recovering addict in the suburbs. I got my drivers license back and bought an old car which I even insured. I still vividly remember that day. I excitedly told my friends in NA that, “I am driving legal!” I was making some progress in other areas of my life, too. I began dating a woman I met at a NA meeting, and for the first time in my life, I was not rushing into things or trying to control everything. Previously, when it came to women, I had a history of “taking a hostage” rather than simply going on a date. Through my involvement in NA, I was learning how to act like a human being. I was having a “spiritual awakening” as a result of working the 12 steps of the NA program and this was apparent to all from my new behaviors.

I continued to work on my recovery issues, as well as working my job as a drug counselor. In April 1995, I married the woman I had met at the NA meeting several years earlier. With marriage, my world was expanding. Together, we bought a house and established credit. I felt pride as I planted roots in my community. I became interested in politics again and I started voting in both the local and national elections. My wife and I developed a concern for disadvantaged people from all walks of life and we became involved in a wide variety of socially relevant activities, for example, doing NA volunteer work in jails and prisons, feeding the homeless, donating money to charity, and collecting clothing for the needy.

I also became actively involved in rescuing stray cats! I used to hate cats! My new lifestyle was a million miles away from anything I had ever done during my active addiction. I was feeling at peace with myself and feeling content with the world at large. The GED that I attained in the halfway house opened the door to higher education for me. I eventually obtained the credentials of Certified Clinical Supervisor and Certified Gambling Counselor. I was elevated to a management position at the counseling agency where I worked at and I began to supervise the clinical staff.

During the last few years, I developed a hunger for continuing my education and I enrolled in college. I received my Associates Degree in 1999 and my Bachelor’s Degree in the spring of 2001. I am now in a Masters program for clinical psychology and I am “tickled to death” with the opportunities that await me.

I owe the NA fellowship my gratitude for restoring my life and allowing me to grow and prosper. By the grace of God and the NA fellowship, I have not picked up a drink or a drug since January 15, 1991. Since then I have come to know and respect many addicts, who, like me, have struggled with the inner demons of addiction and went on, despite the odds, to become drug-free, productive members of society.

This thesis will explore that recovery process. My research question, “What is the experience of transitioning from drug addiction and criminality to becoming a drug free productive member of society?” will be further elucidated in the following chapter through my in-depth analysis into this personal question.

Mike M.

Send Mike M. email!

personal stories

Send Intervention.org email!

- Pepe Acuna

- Steve A's Story

12.20.2009

- Paradise Lost, Living, Dying and living again in Paradise Don S's Story

12.20.2009

- Adam K. - I grew up in Washington, D.C. I had every opportunity anyone could want.

I grew up in a nice house in Georgetown, I had parents who loved me, and I went to one of the best private schools in the area.

11.20.2009

- Chris M. - I am the third of six kids. Grew up in Rockville, Md.

11.19.2009

- Michael M. - Transitioning from Drug Addiction and Criminality to Becoming a Productive Member of Society

1.19.2009

- REE'S STORY FROM PARADISE-THE FLORIDA KEYS.

2.12.2008

- Ken's Story - I started using when I was 10 years old, the drug was alcohol. .

5.11.2007

- Terry's Story - I kept starting meetings all over NY City because I found a home in Narcotics Anonymous and freedom from active addiction.

2.23.2007

- Roger Teague

- Keith's Story - Clean at 17

1.15.2007

- Rajiv's Story - Our past good deeds bear their good fruits

12.16.2006

- William's Story - Radical Surgery

3.22.2006

- David Moorehead

- Jody's Story

2.14.2006

- An LSD Experience

1.08.2006

- Scott Gilbert

- Meridith Edwards

- Lou Popham

- Raphael's story

1.03.2006

- Lynne's story

12.28.2005

- Annie's Story

11.19.2002

- Dee Dee Ramone

- Introduction to the Rape Stories

02.01.2004

- Vickie's Road to Recovery

- The Methadone Perspective from 16 Recovering Addicts

- Photographic Memories

- Addict Review

- Samantha's story

- Debbie's story

- Willie's story

- Mimi's prison release talk

- Yolanda

- Daisy's experience

- Bob Berg

- Mary's Stories

robert barrett blogspot

- Robert's Stories

a boy's story - The Spirit of Innocence The Gift of Sight

- Chris's Interview 2001

- Chris Keeley's Social Documentary Photography

Photographic Memories - Arts - Washington City Paper

Out of the Dark

Art

In to the Light

Art

Flashlight Artist

Art

Heroin Times

Art

Hey Wonderful Person, be Happy Joyous and Free.

If you are an addict ?

You Don't need (have) to S M O K E anything , EAT healthy ,

Don't DRINK any Methadone , Moonshine

or SWALLOW any PROZAC, Zoloft, Paxil, Effexor, (ANTI-depressant) tablets , SSRI (Selective Serrotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), Luvox (OCD),

HUFF Anything, Take X

or use any of the new drugs that are being invented everyday,( Anti-Anxiety Drugs, Anti-Psychotic Drugs, Anti-depressant Drugs, Mood Stabilizing Drugs).

The PDR keeps getting fatter each year,

the answer is

Spiritual not Chemical

TRY GOD (SPIRIT) instead

stay clean and find a new way to live ,

there is hope for any addict.

You are no different,

we can survive our emotions clean together and grow. TRY clean first.

The chances are you are the problem and and total abstinence is the cure. Changes will happen overnight.

Once you are clean and you still can't face life without drugs, then any psychiatrist can load you up

with the latest chemical and the viscious cycle will progress to misery,

degradation, dereliction, jails , institutions and death.

If you keep doing what you are doing, you'll keep getting what you are getting.

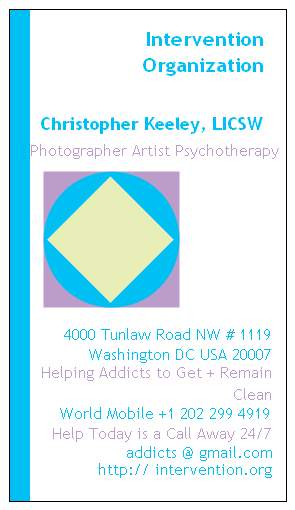

Help is a call away.(202) 299-4919 .

The Last time miracle growth occured on any of these pages was around 12.28.2009…

Have a great Day!

And remember God (SPIRIT) Loves You

- Daily DreamTime

Catskill Mountain Photographs

Catskills Mountain Photographs

one

Catskill Mountains Photographs

two

Early Work

Art

May Isabel Medina Govin

Pureblood

Photograph art series

© Keeley 1991

Art

Pureblood 2

Photograph art series

© Keeley 1991

Art

Collage 1987 a

Art

Collage 87 b

Art

Collage 1987

Art

- User: addict | LibraryThing

artmuseum

Chris Keeley's

Art Galleries

- Art Resume

- Work Resume

- Photographic Memories

- Addict Review

- Sifnos Review

super cool links

Chris keeley's resume

secret surrealist society artwork

dead friends

newest sss art

Chris keeley's art galleries

rationalize,minimize and denial statements

the Intervention Organization

five and ten press - consulting iconoclast

Narcotics Anonymous recovery links

Narcotics Anonymous Recovery

Chris Keeley's Social Documentary Photography

activism

Art links

Big brother

Blinded by Science

Darkside / Gothic

Dharma Road

G E E K

Maul

Music

Pirate

radio

W E I R D O

What's Mailart

Mailart List

Scanner Links

Drugs

- Drug addiction

- Debbie's Journey

Photographs

Art

Out of the Dark

Art

In to the Light

Art

Return to Intervention Home Page

![[INLINE:ONDRUGS]](ondrugs.gif)