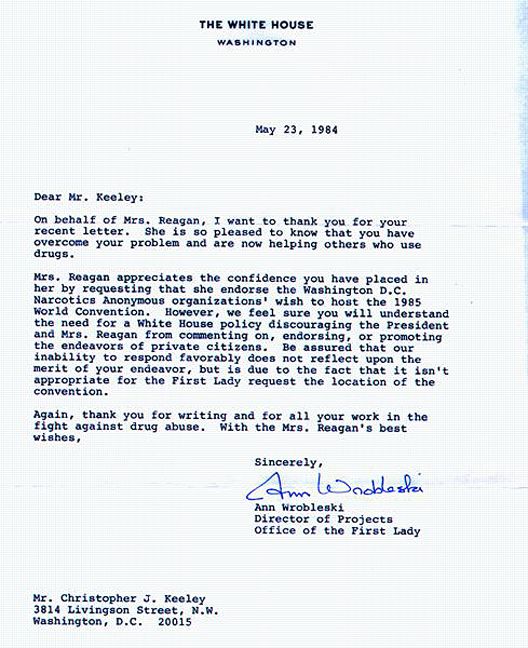

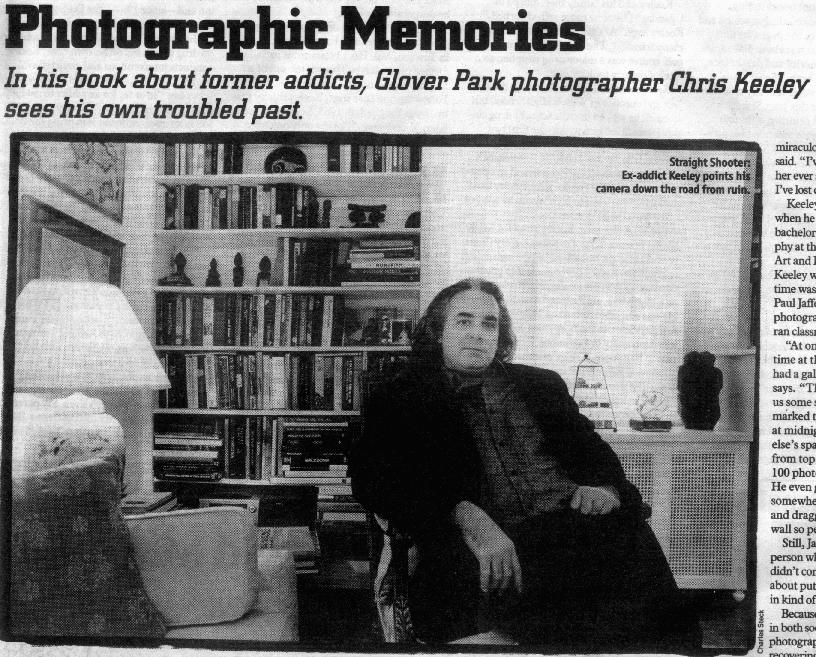

Photographic Memories

All Photographs + Text Copyright 2025 Christopher Keeley

Photographic Memories

In his book about former addicts, Glover Park photographer Chris Keeley sees his own troubled past.

By Louis Jacobson

The first of the 51 narratives in the book Addict: Out of the Dark and Into the Light tells the harrowing yet inspiring life story of Trayceous Klein of Reno, Nev.

Matter-of-factly, Klein tells her interviewer how she had begun to drink and pop pills by age 11. Klein later ran away to San Francisco, where she lived on the streets. Back in Reno a few years later, she became romantically involved with another hard-core drug abuser. One Saturday morning, Klein took several bottles worth of pills, washed them down with tequila, and headed to her boyfriend's drug den to die. The boyfriend, worried that investigators would discover his stash if she died at his place, put Klein's limp body into her car, turned on the motor, and left her.

Discovered by a passer-by, Klein was rushed to the hospital, where she remained in a coma for several days. She recovered and, horrified by what she had become, swore off drugs on Independence Day 1985a pledge that she kept through the date of her interview in 1988. Since she had been adopted and was never sure of her real birth date, Klein began celebrating her birthday on July 4. Just when you think everything is lost, it seems like something new is around the corner, Klein said.

Chris Keeley a social worker and drug counselor who lives in Glover Park was the person who interviewed Klein and the other 50 subjects of Addict. Although Keeley claims he doesn't like to play favorites, Klein's story, he says, may have moved him the most. Its just a classic tragic story that ends up with a miraculous recovery, Keeley said. I've been trying to find her ever since I did her story. But I've lost contact with her.

Keeley began Addict in 1987, when he was studying for a bachelors degree in photography at the Corcoran College of Art and Design. Everything Keeley was working on at the time was very intense, recalls Paul Jaffe, an Arlington-based photographer who was a Corcoran classmate of Keeley's.

At one point during his time at the Corcoran, we all had a gallery showing, Jaffe says. The gallery gave each of us some space on the walls and marked them. So Chris goes in at midnight, takes someone elses space, and wallpapers it from top to bottom with about 100 photographs hed taken. He even got a bench from somewhere else in the museum and dragged it in front of his wall so people could sit down.

Still, Jaffe says, even the person whose space he stole didn't complain. [Keeley] went about putting the book together in kind of the same way.

Because Keeley was interested in both social activism and nude photography, he asked some recovering addicts he knew whether they'd be willing to pose for his camera. At some point, Keeley decided also to tape them as they related the stories of their addictions and recoveries. When a few subjects told him that they were happy to unload their stories but not their clothes, Keeley dropped the nudity requirement. He then decided to turn the project into a book.

Keeley gathered names of potential interviewees from the recovering addicts he knew. He then traveled the country at his own expense to interview them, accompanied by a bag full of cheap 30-minute cassettes. The only requirement for inclusion in the book was being clean. Only about 10 people turned Keeley down; the rest provided him with enough material to fill 387 densely packed pages.

I didn't look at it as a way to make my star rise, recalls Marc Burkhardt, who kicked the habit in 1979 and posed nude for Keeley's book. He was interested in doing something to show how recovery had occurred in peoples lives. I looked at it as being a very cool thing.

For a year, Keeley worked on the book on a daily basis. When he finished it, he sent inquiries to roughly 50 publishers but struck out everywhere. So in 1994, he asked his friend Bo Sewell if Sewell could help him print the book privately. Sewell another recovering addict, though he isn't profiled in the book knew very little about publishing, so he went to the public library to borrow some treatises about bookbinding. Sewell then built a bookbinding machine and found someone to print the pages for him. The first run of Addict was about 500 copies.

All it took was temerity and persistence, and we had plenty of both, Sewell says. Every one sold. We never had any trouble selling them. Earlier this year, Sewell churned out a second printing, although Keeley says that he never intended his project to be a moneymaker.

The purpose of the book was to help people understand addiction and to humanize the stigma of addiction, Keeley says. I wanted people to know that it's a disease and that anybody can recover. One day, I want to give every member of Congress the book, so they understand that its a medical problem, not a criminal problem.

One group the book was not designed for is addicts. Addicts, Keeley says, already know.

Keeley himself knows addiction only too well: For more than a decade, he got high in one way or another virtually every day. He says he nearly died on numerous occasions, but on Dec. 28 of this year, Keeley will celebrate his 17th anniversary of sobriety. Since breaking the habit, he's treated countless other addicts as a drug counselor.

Jaffe, who semijokingly calls his friend a self-centered egomaniac, gets a chuckle out of the irony that Keeley never included his own story in his book. Asked why he didn't, Keeley explains that he was using all the other people as my own story. My story would be a whole book in itself.

Keeley, 43, grew up in a series of exotic locales as a diplomat's kid. His run-ins with the law began in first grade, when his family was living in the District. That year, he set off fireworks that landed on a nearby veranda, torching it. Later, when the Keeleys lived in Greece, he smoked cigarettes, drank wine, shot off tear-gas capsules, and destroyed a school water fountain with fireworks. Sometimes he stole money from his parents to rent minibikes.

When Keeley was in junior high school, his family spent a year in Princeton, N.J. Keeley would cut school to get high on the Princeton University campus. I was already a little revolutionary hippie radical, Keeley says. I had cut the American flag into strips and hung it in my doorway. My mother almost had a heart attack, and it was offensive to my father. She made me go burn the flag and bury it.

Keeley and his family then moved to Uganda. I became more self-absorbed, Keeley says. At that point, I didn't have many friends. The chief caddy at a nearby golf course was a major drug supplier, so Keeley eagerly took up golf.

Keeley returned to Washington in the mid-70s and enrolled in Wilson High School, but as usual, he tapped into the school's drug culture which led him to skip the final two months of 10th grade. The next year, Keeley attended the Barlow School in Amenia, N.Y., which offered an art curriculum and an open-minded educational philosophy. Keeley liked the focus on art, but to his chagrin, he was not asked back the next year.

For his senior year, Keeley attended Sandy Spring Friends School in Montgomery County. But although he had earned enough credits to graduate, Keeley never made it to graduation day. Late in his senior year, Keeley went on a marijuana, alcohol, and cocaine binge. He was rushed to Suburban Hospital and, a few days later, to the hospital at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. However, on the ride to Baltimore, Keeley punched out the window in his parents car and escaped. Before he was discovered, he drank enough alcohol to knock him out.

Once deposited at Johns Hopkins, Keeley managed to escape after only two months of rehab. At that point, I was ready to abandon my parents and go to California to live a life of crime or whatever, he recalls. After a reconciliation, his parents agreed to let Keeley enroll in American University, but he lasted only a year and a half until his GPA dropped to .04. At that point I was suicidal, he says. I wrecked about four cars and lost my driving privileges. I became addicted to opiates, heroin, Dilaudid. That lasted until I was 25.

Keeley then bounced between the United States and his father's posting in Zimbabwe. I basically led a double life, he says. I was a safari guide in Zimbabwe for nine months, but I was still getting high on the side. When he was fired from the safari job, Keeley says, I guess I realized that I was so far gone in my addiction that I couldn't see any way out. I had no courage to ask for help.

A drug-induced coma led Keeley to another trip to Johns Hopkins, but he began sneaking drinks just a few weeks after waking up. When the hospital expelled him, his parents finally gave Keeley an ultimatum: Go back to drug rehab or hit the streets of Baltimore. It was harsh, but in retrospect, Keeley says, it proved to be the turning point he desperately needed.

So Keeley entered a drug-treatment program at Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital in Towson, Md. His 13 classmates included a former pro basketball player, the son of a Mafia lawyer, and a Baltimore prostitute. Following one false start, Keeley finally gave up drugs for good, in 1983. Seventeen years later, Keeley says, I'm the only one from that group of 13 who's alive and clean.

Keeleys gradual recovery was aided by his interest in photography. He initially enrolled in one course at the Corcoran, but his professors soon encouraged him to attend full time. Eventually, he earned his bachelors degree; he began to exhibit his social-documentary images in 1985.

An early series explored youthful alienation and suicide. Another series, about the homeless, was displayed in a 1990 solo show at the Cannon House Office Building. Keeley's photographs of the homeless also formed the basis of a video and slide presentation now used by the National Coalition for the Homeless; 2,000 groups around the country have seen it, Keeley says.

Keeley's sister, Michal Keeley, a Washington editor with the online magazine Salon, gives art at least part of the credit for keeping her brother clean. If you're going to overcome addiction, you need something like [art], says Michal. It helped [his recovery] to have talent and inspiration.

Keeley himself isn't so sure. My recovery is personal, he says. I am obsessive and compulsive, like most artists. Maybe [art] helps, I've never thought about it. What helps my recovery is helping others unconditionally. It reminds me of where I came from and where I could go.

Keeley has had several dozen individual and group shows in Washington and elsewhere. And since 1996, 16 portraits from Addict have been posted (with accompanying sound files) at

. Much of Keeley's other work is viewable on his own Web page,

.

In addition to his photographic pursuits, Keeley has been employed full time in drug counseling and social work since 1988. He first worked with a diversion program that puts first-time drunk drivers into treatment rather than jail. He has since been employed by the Community for Creative Non-Violence, the Psychiatric Institute of Washington and since 1997 the D.C. governments Child and Family Services Agency.

His current job doesn't include much work on drug abuse, but on his own time, Keeley conducts interventions and gives referrals. And his Web site, he says, gets as many as 500 hits a day. In order for an addict to get help, they have to hit bottom, Keeley says. My job as an interventionist is to bring the bottom up and eliminate enablers.

Keeley says that his experiences as an addict give him a leg up in understanding his clients. Even so, he says that he doesn't often broadcast his background. Most of my clients dont know about my past, he says. I would only tell my past to someone if I thought it would be an instrument to help them. A lot of times, my personal life would interfere professionally with what I'm supposed to be doing.

A similar line of thinking motivated his decision not to include himself in Addict. Only now is Keeley beginning to tell his story to the wider world. I pretty much wanted to remain anonymous [in Addict], he says. I didn't want to hurt my family. One day, I do plan to do my own story, maybe a movie...about the horrors and amazing escapades of addiction, using my life or a combination of peoples lives.

My parents are now proud of me. My life has done a 180-degree turn. I have gone from being a taker to being a giver.

Chris Keeley Washington DC

Photograph � Charles Steck 2000

Addict Out of the Dark and into the Light

Hardback ISBN:

1-4257-7889-5

Hardback ISBN 13:

978-1-4257-7889-7

Click here to view an excerpt from the book.

I wanted to get the message out that any addict could get clean, stop using drugs and find a new way to live.

My personal life experience can be a living example to help educate the public that addiction is a humanistic

disease from which the addict and family members suffer no matter what supportive opportunities are given. The

disease of addiction is completely profound in the aspect that help can only be obtained through a miraculous

process of Recovery otherwise known as Grace. I share about the horrors of my life and how wonderful my

life has become today. In the spirit of recovery my contribution is exemplified by the selfless effort of helping

other addicts find and achieve recovery. Today my goal is to help others unconditionally and to be a part of the

solution rather than the problem. My understanding is my contribution will help alleviate the pain and suffering

of addicts and those close to addicts by being exposed to this work of art. My motive was to bring to light the

love and truth about the feelings of an addict who has found joy, happiness and freedom. This is the recovery

revolution that is going on right now.

- Chris Keeley

Copyright 2006 by Christopher Keeley

ISBN 10: Softcover 1-4257-3634-3

Softcover - $48.99

ISBN 13: Softcover 978-1-4257-3634-7

Hardcover - $65.32

ISBN not available yet

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

To order additional copies of this book, contact:

Xlibris Corporation 1-888-795-4274

www.Xlibris.com

Orders@Xlibris.com

A Stunning Memoir about Recovery from Addiction

Author Christopher Keeley offers hope for drug addicts to get clean, to start over, and have a wonderful life

Washington, DC. 02.08.2007, Addiction to drugs is like a lover that you crave for, the more you

give in to it, the harder it is to let go. This unhealthy obsession can cause horrible

consequences, not only to yourself, but also to your family and the people you care about. Author and

award winning photographer Christopher Keeley shares how he quit this nasty habit through Paradise

Life, a profound collection of personal stories and photographs that inspire a spirit of recovery.

Paradise Life is the author's personal memoir of an addict overcoming addiction and the miracle of

recovery. Keeley's photographs deal with the many facets of obsession and speak to the internal search

many individuals undergo during the lifelong quest for meaning and selfawareness. Drawing on his own

inner obsessive quest for knowledge as inspiration, Keeley captures pain, longing, torment, despair,

hope, and love within the faces and forms of his images. His pictures are unsympathetic and

communicate the inner emotional trauma of the homeless, the addicted and the lonely as well as the

strength of human bonding experienced by addicts in recovery. By revealing the essence of his

subjects, the works magnify with often unsettling clarity the pain of discovery, joy of friendships

born of pain, or the turmoil of new journeys that resound within each person. Through these poignant

images, Keeley challenges the viewer to look within one's own heart to question, affirm, accept, or

reject, leaving one with valuable insights into our own places in humanity.

Keeley declares that any addict can get clean, stop using drugs, and find a new way to live, offering

his personal experience as a living example. He aims to help educate the public that addiction is a

humanistic disease from which the addict and family members suffer, no matter what supportive

opportunities are provided. The disease of addiction is completely profound in the aspect that help

can only be obtained through a miraculous process of Recovery otherwise known as Grace. As he shares

the horrors of his life and how wonderful it has become today, he hopes to help alleviate the pain and

suffering of addicts and those close to addicts by being exposed to his work of art. Paradise Life

will bring to light the love and truth about the feelings of an addict who has found joy, happiness

and freedom.

This memoir is an excellent resource for all Professional Healers or Health Care Providers. Health

Professionals, Educators and Health Services Administrators would benefit from Paradise Life.

Advocates, Addiction Therapists and Mentors would also benefit from Paradise Life. A must read for any

human being who cares about other human beings.

About the Author

Christopher Keeley is a resident of Washington, DC. He holds a master's degree in social work (National

Catholic School of Social Service) as well as a bachelor's degree in fine arts The Corcoran School of

Art. Since 1997 the author has been working as a social worker supervisor in the child abuse and

neglect family Court system of Washington DC. Keeley has appeared several times on television and

continues to be active in photography. He has exhibited his social documentary photography

internationally. He has won several awards for his work.

Paradise Life * by Christopher Keeley

Publication Date: February 8, 2007

Trade Paperback; $48.99; 160 pages; 978-1-4257-3634-7

Cloth Hardback; $58.99; 160 pages; 978-1-4257-5080-0

To request a complimentary paperback review copy, contact the publisher at (888) 795-4274 x. 472.

Tearsheets may be sent by regular or electronic mail to Marketing Services. To purchase copies of the book

for resale, please fax Xlibris at (610) 915-0294 or call (888) 795-4274 x. 876.

For more information, contact Xlibris at (888) 795-4274 or on the web at www.Xlibris.com.

Library of Congress Number (if applicable): 2007900278

Photographic Memories - Arts - Washington City Paper

Photographs

Art

Out of the Dark

Art

In to the Light

Art

super cool links

Chris keeley's resume

secret surrealist society artwork

dead friends

newest sss art

Chris keeley's art galleries

rationalize,minimize and denial statements

the Intervention Organization

five and ten press - consulting iconoclast

Chris Keeley's Social Documentary Photography

activism

Art links

Big brother

Blinded by Science

Darkside / Gothic

Dharma Road

G E E K

Maul

Music

Pirate

radio

W E I R D O

What's Mailart

Mailart List

Scanner Links

Drugs

Photographs

Art

Out of the Dark

Art

In to the Light

Art

Collage DaDa

Art

Send me email!

Return to Intervention Organization